CopShock: Second Edition

Surviving Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

by Allen R. Kates, MFAW, BCECR

Sex Addiction in Police Officers

As A Result of Stress and Trauma

Written by Allen R. Kates, MFAW, BCECR

Complete chapter as published in Stress Management in Law Enforcement, Third Edition (2013)

Edited by Leonard Territo, James D. Sewell. Carolina Academic Press

ISBN: 978-1-61163-111-1

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to throw a spotlight on sex addiction in police officers as a result of overwhelming stress and the inability to cope with traumatic incidents. As this is a relatively new area of study, this exploration lays the groundwork for further study, screening and treatment.

Sex addiction has been in the news on a regular basis ever since former President Gerald Ford called former President Bill Clinton a sick sex addict in a 2007 book published after Ford’s death.

Ford, whose wife started the ultra-chic Betty Ford Center that treats alcoholism and addictions, including sex addiction, said Bill Clinton’s, “... got a sex sickness... He’s got an addiction. He needs treatment.”1

Many other politicians, actors and athletes have admitted to sex addiction or have been “outed” in the press.

Among the well-known alleged sex addicts are golf phenomenon Tiger Woods,2 actor and former California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger,3 Major League baseball player Wade Boggs,4 and presidential hopeful John Edwards.5 Still, we must view the accusations with a degree of skepticism. The evidence of their sex addiction is sensational but flimsy, even that of self-described sex addict Tiger Woods. Is he really a sex addict or a spoiled brat who locked himself away in a sex recovery treatment center in an attempt to save his marriage?

Before the term “sex addiction” was coined, people who compulsively switched sexual partners with abandon were often condemned as promiscuous, immoral, oversexed, aberrant and whorish. Sometimes they were also admiringly called rakish, bawdy, ribald, raunchy and profligate—as if irresponsible and reckless behavior was condoned as just boys sowing their wild oats or being young and stupid. They acted like frat boys who would soon grow out of their wacky ways and join the world of serious thinkers and doers.

Whatever you wish to call it, indiscriminate sexual activity with no concern for hurting their sexual partners, having unprotected sex, spreading sexually transmitted diseases, or making unwanted children, has serious consequences.

Definition and symptoms of sex addiction

Not many studies have been written about sex addiction in general and almost nothing about how it affects law enforcement officers. The American Psychiatric Association, in its diagnostic bible called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), is struggling to come up with a workable definition of sex addiction and may ultimately decide to ignore it.6

However, a handful of mental health researchers have developed what they believe are practical definitions.

Failure to control sexual behavior

Significant harmful consequences

In a thorough study described in Psychiatric Times, Dr. Aviel Goodman, director of the Minnesota Institute of Psychiatry, says that sex addiction may be “characterized by recurrent failure to control... sexual behavior” which continues “despite significant harmful consequences.”7

Tolerance over time

Withdrawal when deprived

In an insightful ABC News story titled, “The Tiger Woods Effect,” the definition of sex addiction may include symptoms usually attributed to drug or alcohol addiction such as a “building up of a tolerance over time” (leading to more frequent sexual encounters) and “going through withdrawal when deprived.”8

Compulsive behavior which interferes with normal living

Causes severe stress on family, friends, peers

Dr. Patrick Carnes, the most prominent voice in the field of sex addiction, author of Out of the Shadows: Understanding Sexual Addiction (1983), the first book to help sex addicts, more broadly defines sex addiction as “any sexually related, compulsive behavior which interferes with normal living and causes severe stress on family, friends, loved ones and one’s work environment.”9 That definition describes situations many police officers find themselves in.

Heart racing, adrenaline pumping

Intense, emotional arousal

Self-soothing, emotional calm

To further depict how police officers experience sex addiction, (although police officers were not the focus), Robert Weiss, LCSW, CSAT-S, Director of Sexual Disorders Services for Elements Behavioral Health and founding director of the Sexual Recovery Institute in Los Angeles, says that:

“(Sex addicts) are going in with an intense fantasy—his heart is racing, his adrenaline is pumping. They are in it for the intense, emotional arousal that provides them with a self-soothing, emotional calm. If you put yourself in a situation of danger, the response would be distracting, but it’s soothing to them... It’s like being in a trance...”10

Vicious cycle of stress, release, shame, anxiety

Mr. Weiss states that “the compulsive behavior is triggered by anxiety, and continues in a vicious cycle of stress, release and then shame, which ignites the anxiety again... ”11

Obsessive

Loss of control

Excessive effort in pursuit

He adds that “(Sex addiction) has an obsessive quality. Like any addiction there is a loss of control.” He says that a sex addict will spend an inordinate amount of time “looking and in pursuit” of his (uncommonly, her) sex object, but the least amount of time in the actual sex act.12

Statistics

Until more in-depth research is conducted, the small amount of data available suggests that sex addiction is a genuine problem. The Society for the Advancement of Sexual Health (SASH) estimates that 3 to 5 percent of Americans, most of them men, are sex addicts. Based only on people who seek treatment, the estimate is considered low.13

Why sex addiction is not described yet in CopShock

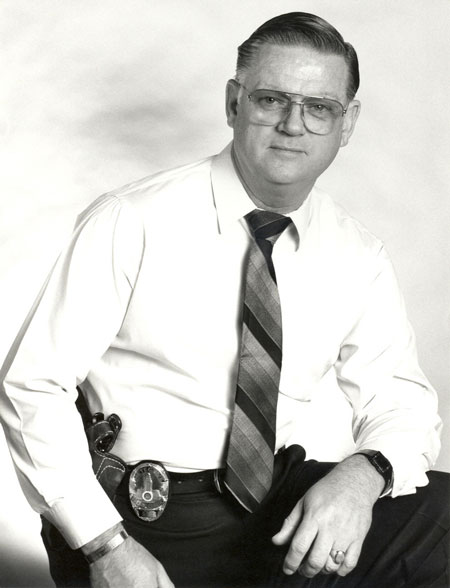

I began researching the first edition of CopShock, Surviving Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in 1993, and for six years interviewed hundreds of police officers about their traumatic experiences, addictions, PTSD diagnoses, regrets, and successes. Many spoke of acting out sexually. No one talked of sex addiction then. For instance, LAPD Detective Bill Martin doesn’t talk of sex addiction in CopShock when he describes his broken marriage, PTSD symptoms and irresponsible sexual behavior. Bill was addicted to prescription drugs and alcohol throughout his 33-year police career. He used drugs and booze to dampen flashbacks of bloody crime scenes and images of dead bodies.

For instance, LAPD Detective Bill Martin doesn’t talk of sex addiction in CopShock when he describes his broken marriage, PTSD symptoms and irresponsible sexual behavior. Bill was addicted to prescription drugs and alcohol throughout his 33-year police career. He used drugs and booze to dampen flashbacks of bloody crime scenes and images of dead bodies.

He was always involved with groupies he picked up at cop bars. As he says, “All I wanted to do was get screwed up and loaded. When my dick was hard I didn’t give a damn. I fucked anyone, anytime, anyplace and I gave no thought to sexually transmitted diseases.”14

During and after his first marriage, he had a long-term relationship with a prostitute. One night at a police academy party, he had sex with the woman while they were dancing—in plain view of other officers and their dance partners. He admitted it was very risky behavior, but he couldn’t stop himself.

As a child, Bill was severely beaten by his father for years, and when he was a teenager, he was raped by a man he thought was his friend. According to definitions of sex addiction, childhood physical, sexual or emotional abuse can set someone up for indiscriminate sexual encounters in the future.15

Even while I was researching the second edition of CopShock a few years ago, sex addiction, although emerging as a contested psychological field, had not become the darling of tabloid media and pop news, hammered relentlessly into our heads. It wasn’t until Tiger Woods’s 2009 revelations of sordid sexual exploits and a bout in a sex addiction treatment center that the term began to capture our collective imaginations.

Most police officers cope well with stress and trauma

So there’s no misunderstanding, I am not branding all police officers as sex addicts. Most police officers handle stress and trauma just fine. They demonstrate healthy coping skills and do not attempt to manage their problems by self-medicating through alcohol, drugs, gambling or sex. They do not become cynical or hopeless, but approach each day with renewed energy and optimism. Even so, some do not know what to do after being shattered by a traumatic incident.

After all, police officers are human beings just like everybody else, and yet they see more horror in one year than most human beings see ever. It is no surprise that when overwrought some may engage in harmful coping mechanisms that make them feel better, but put their lives and the lives of innocent people in jeopardy.

Case history of a sex addicted police officer This case history16 describes the life and law enforcement career of Alex Salazar. He worked for the Los Angeles Police Department for nine years, from 1990 to 1998. He started in Rampart Division as a rookie, went to Wilshire Division after about a year, and about three years later moved on to Southeast Division, Watts, where he became an undercover officer on the South Bureau Narcotics Undercover Buy Team. He worked undercover narcotics for about four years, a long time for anyone that fears he could be found out and killed.

This case history16 describes the life and law enforcement career of Alex Salazar. He worked for the Los Angeles Police Department for nine years, from 1990 to 1998. He started in Rampart Division as a rookie, went to Wilshire Division after about a year, and about three years later moved on to Southeast Division, Watts, where he became an undercover officer on the South Bureau Narcotics Undercover Buy Team. He worked undercover narcotics for about four years, a long time for anyone that fears he could be found out and killed.

Family upbringing

Alex was born in Hollywood, California, and grew up primarily in Azusa in LA County. After graduating high school, in 1986 he joined the U. S. Air Force, where he became a security specialist in Central America and then England. In 1989, he attended the police academy.

He grew up in a zealous Catholic household. He said that his family was like the “Mexican Brady Bunch” where his parents were good role models. “My mother was into whipping our asses and was a very strong disciplinarian.”

Saw many dead bodies

After attending the police academy, in May 1990, he started work as a rookie in the LAPD’s Rampart Division. About a year later, he married his high school sweetheart, a woman with whom he had a long, loving relationship.

Rampart was a busy division. From the moment Alex arrived and logged onto the MDT, mobile digital terminal, “our calls would light up. There would be a Code 2 urgent call, assault in progress, man with a gun shooting.” He investigated multiple homicides, beatings, rapes and robberies, going from one to another without processing emotionally what he had seen or done. He saw more bodies in one night than a mortician saw in a week. But the work was exciting and Alex didn’t feel that he needed counseling. Nobody else did, so why should he need it?

He saw other cops involved in risky sexual behavior

Although he liked to have fun, he was dedicated to his wife and their marriage. Everyday he saw police officers who were single or married having affairs and engaging in heavy drinking and risky sexual behavior. Alex didn’t like drinking, but attended Choir Practice in local police bars along with other cops as a way to decompress and have a few laughs after a tour of mayhem and madness. He sipped one drink the whole night, shared war stories and listened to tales of sexual derring-do. He watched other cops dancing, petting, and groping.

Groupies at clubs

On and off duty, he and his partner cruised the clubs and dropped in to see if any illegal activities were going on. At Club Vertigo, “women would surround us and give us their phone numbers. I said ‘I don’t need this. I got a wife, I’m happily married.’” According to Alex, his partners were not so averse.

Work hard, party hard

Alex said “the ethos was: You work hard, you party hard. That meant arresting gangbangers, going to bars, getting drunk off your ass.” He said that some officers shot out streetlights after a night of drinking and carousing.

Although he thought he was like any other cop, Alex did not engage in promiscuity or wild behavior. That is, until he had what he calls his “incident.”

Alex attacked, injured. No one helped.

On September 28, 1991, after he had recently moved to Wilshire Division, Alex was out shopping and witnessed a woman struggling with a man attempting to rob her at Broadway and 8th Street. Alex got out of his car, chased the man down, identified himself as a police officer and grabbed him by the arm. As the man was not resisting, Alex didn’t pull his backup .38. He instructed the woman to call 911 for help.

After she left to find a phone, a crowd, including a number of gang members, gathered around Alex and his prisoner, and shouted at him to let the guy go. Someone pushed Alex from behind and the suspect took off. Then about six men threatened to beat him. Some swung belt buckles. Alex stepped off the curb, pulled his .38, and told them to back off. The gun had no effect and they continued to advance on him.

Suddenly, a passing car hit him and ran over his ankle, breaking it. Although badly injured, lying in the street, nobody helped him. The gangbangers then looted his car, smashed out the windows and kicked in the doors. A few minutes later, several black-and-whites roared onto the scene and ended the attack.

Alex was rushed to the hospital and underwent surgery where a metal plate and screws were inserted to support his ankle. He was off work for about four months.17

Turning point: nightmares, flashbacks, anger, suicidal thoughts

This was a turning point for Alex. He was 25-years-old, but no longer the happy, carefree man he once was. His previous unresolved traumas infected his dreams, and gave more power to his nightmares and flashbacks of the attack. In his mind, he kept replaying being run over, a common response to a traumatic incident.

“I was helpless, lying in the middle of the street, no one coming to my aid,” he said. He was angry all the time and felt that the department didn’t care. He had suicidal thoughts and went to see the department’s psychologist on a regular basis, but felt he wasn’t getting anywhere.

He didn’t care anymore

A few months after Alex’s traumatic incident, he felt that he didn’t care about anything or anybody any longer. “I didn’t give a fuck anymore,” he said. “Up until then I had always done everything right.”

Development of sex addiction

The stress and disillusionment pushed him toward looking for new ways to cope. He didn’t have to look far for role models. Many of his fellow officers were engaged in dangerous sexual encounters and, before long, Alex became involved in them, too.

It seemed that the more stress he was under, the more he pursued strange women for sex. The more women he had, the more he wanted, and his thoughts and conversations with other officers were habitually consumed with the acquiring and bedding of multiple partners.

Drinking heavily

Within months after his traumatic incident, Alex was drinking heavily and carried a small metal flask. Although he hated the taste of liquor, he needed something to relax him and dampen the traumatic images running around in his mind.

He especially liked to add Bacardi 151 rum, a high proof liquor nearly 76 percent alcohol, to an extra large Coke.18 Although he would grimace at the taste, he knew it would give him the high he wanted.

“I was more of an alcohol abuser than an alcoholic,” he said. “I didn’t like the feeling of being drunk and throwing up. My whole goal was to get relaxed, go to bars, to the clubs, and not be so tense and hypervigilant. That loosened me up for all the sex antics.”

Hypervigilance

When police officers are hypervigilant, they are aware of threats around them. That can save their lives. But when hypervigilance goes to an extreme, officers become hyperaware of everyone. Instead of determining who is a threat and who isn’t, everyone, good person and bad, is perceived as a threat. As a result of his traumatic incident, Alex had become hyperaware, overly hypervigilant, a PTSD symptom that causes continuous adrenaline rushes and leads to exhaustion. Alex sought to reduce his hypervigilance through sex.19

Badge bunnies

Despite loving his wife, Alex began sleeping with other women indiscriminately. He said his wife wouldn’t listen to him when he tried to explain the turmoil inside himself. Consequently, he went looking for “badge bunnies,” groupies that hung out at police bars.

Impregnated wife and groupie, got gonorrhea

After about three years on the force, Alex was out of control, searching for one conquest after another. Half the time, he did not use protection when he was out with women he had picked up “because I had that I-don’t-care attitude. After I got my ass run over and almost killed, my whole decision-making processes were bad. I was led by my emotions, by my anger. I wasn’t rational,” he said.

“I got my wife pregnant and at the same time got another woman pregnant and she gave me gonorrhea.”

Alex asked the woman to have an abortion, but she refused. He did not give gonorrhea to his wife, but, after a while, she found out what he’d been up to. He didn’t care.

“I had become selfish, self-centered,” he said. “It was all about ME now. I was no longer going to be Mr. Perfect. I was not going to do everything everybody wanted me to do. It was all about me fulfilling my selfish desires.”

Children, divorced, sleeping with numerous women

His wife and the woman he got pregnant gave birth at almost the same time. Then, after nearly two years of marriage, he and his high school sweetheart divorced. Despite now being responsible for supporting two children, Alex continued to engage in irresponsible behavior, often having unprotected sex with numerous women.

During his Wilshire stint, he frequented a bar called the Short Stop, a famous police hangout decked out in LAPD memorabilia. He recounts one night that he and his partner picked up two girls and took them to a hotel and “tagged teamed” them. He didn’t want to share because he was not attracted to his partner’s “date,” but he “did it anyway because he was my partner.”

One night he took a girlfriend up to the Hollywood sign. He said, “It was exciting up there by the lights, the crackling of the police radio in the background. I whipped it out and hit her on the hood of the car.”

After he dropped her off, he returned to the police station and the Sergeant yelled at him. Apparently, he had a white stain on his pants around his fly. Alex made up a story about spilling ice cream on himself, and “I got the hell out of there.”

Crash pads for sex

Alex said that the officers had “crash pads” around the division. On occasion, property managers put the word out that they had break-ins and wanted to give officers a free apartment or discount if they would watch the place and keep the peace.

He said that he often had sex with groupies in his car, but would have multiple women visit the crash pad, one right after another. “We set up appointments, even the married guys.”

Code X, on duty booty

The on-and-off-the-job sex was often condoned and covered up by officers at the station. The desk officer kept track of “Code X” calls, an official sounding 10-Code that did not exist. It was made up to fend off wives, girlfriends and superiors trying to reach officers who were supposed to be on duty.

According to Alex, Code X actually meant “Hey, I’m out getting some on-duty-booty.” The desk officer would make up a story saying the unreachable officer was on a homicide, on a call or otherwise unreachable. Then the desk officer called the wayward officer or sent a computer message that his wife or girlfriend was looking for him. It was a professional courtesy recognized by most officers.

All about partying, sex gave him a high, striptease

Alex feels that sex addiction is a cultural thing, police culture, that is. “It seems everybody was doing it. It was pretty rampant. We thought we were powerful. We became very narcissistic wearing the LAPD uniform. It was all about partying, getting your nut off as a way of stress relief.”

He said that police parties were “wild drunken bashes” with lots of sexual activities, especially the Christmas parties. He said he was addicted to having sex with different women because “I felt there was a void within my soul. Having sex, getting drunk, took away the pain and anxiety. I would be angry, depressed and sad. Sex gave me a high.”

To further describe the sex-drenched culture, Alex told me that his training officer once brought his girlfriend down to the station at midnight during morning watch to do a striptease for the guys. “She was a professional stripper and she took everything off. We cheered and yelled, of course. Everybody thought my training officer was the coolest guy.”

Predatory sexual behavior

“We were like junkies,” he said. “We had to have it and went out on the prowl.” Alex said they cruised the bars looking for girls standing outside. They would talk to the girls and persuade them to hook up for sex back at the crash pad after the shift was over.

He went out on calls with a cop who took advantage of female victims of domestic violence. They arrested the husband, and when nobody was looking, the cop stole the husband’s or wife’s ID card. After they booked the husband at the jail, his partner returned to the home to drop off the card, saying he found it. The woman was inevitably in an emotional state. He consoled her, “she was crying and they hugged, and the next thing you know they were having sex.”

In looking back on his actions, Alex said that he didn’t view himself as a predator then. “But I do now because we would go out on the hunt. That’s what a predator does.”

He said the women “came in all shapes and sizes, Hispanic, white, black, Asian, everything. They were young and older, mostly women with low self-esteem. It was women who wanted to hook up with someone or find a husband, someone with a stable job. For predators like us, they were just a piece of meat. It was like putting a steak in front of a dog’s mouth. What’s he gonna do?”

Constant fear as undercover officer, sex as stress reliever

After Alex joined the South Bureau Narcotics Undercover Buy Team, he endured constant adrenaline rushes because of overwhelming stress. He said he would do about three buys a day, working with other undercovers doing more buys. Sometimes guns were put to his head or “I got my ass kicked because gangbangers thought I was from another gang.” He said that he got into shootouts and “I was supposed to come home and act normal?”

He lived in a state of constant fear. Would they find out who he was? Would someone he busted previously suddenly appear? Would the bad guy try to rip him off and shoot him?

Alex learned to lie because if his lies were not believable, he could end up dead. “The stress is so great, your lies must be believable not only to the drug dealer, but also to yourself.”

After a while, Alex began to think and act like the criminals he was trying to put behind bars. “When you look in the mirror, are you the good guy or the bad guy?” he said. “Do I tell my supervisor all the mixed emotions I’m experiencing?” Alex could not reconcile the moral and spiritual conflict warring inside himself, and that clash of opposing attitudes increased his stress. But tell his supervisor? No way. It would make Alex look like he couldn’t handle the job.

He got so good at undercover work that he was promoted to leading the undercover investigators, directing a team of officers. At the end of a day, sometimes they would haul 40 or so people to jail. The increased status and workload contributed to his anxiety, but he did the job for four years, an exceptionally long period of time under extreme stress.

Police officers are sometimes described as adrenaline junkies and Alex lived off the adrenaline high. He said, “I was highly energized and just wanted to screw to get out my frustrations. After you have sex, you feel better. Sometimes we would have sex with two, three, four different women a day.”

Department will use and abuse you

When Alex started in undercover, he was warned by a friend in narcotics that the supervisors and department would “use and abuse you,” and to take measures to protect himself. Alex ignored the advice and the workload kept increasing, along with his stress.

While doing drug buys, his day started at 6 AM when his alarm clock went off. By 7 AM, he was out the door fighting Los Angeles traffic. By 8, he had picked up narcotics evidence and was on his way to court for an 8:30 hearing, sometimes having to testify in the morning and afternoon in different court houses. In late afternoon, he went out on dangerous and often life-threatening drug buys that sometimes lasted until one or two in the morning. Then, with only a few hours of sleep, he’d start his day again. And the next day was the same, and the day after that.

He was pushed to exhaustion, but was afraid to take a stand and say No. He was also warned that those in managerial positions would take credit for his arrests. They did, and that increased his cynicism about the department and perception that it was not supporting him.

Six suicides in four years

After Alex’s traumatic incident, he felt that he was riding a train down a track to self-destruction, but could not stop it. His sex addiction, drinking and carousing were out of control. The few hours he had for sleep were often restless, and he would wake exhausted, facing a day of relentless stress and anxiety about being found out and killed. To add to his cynicism, despair and fear, during a period of just four years, two of his partners committed suicide and four other cops he knew killed themselves.

Alex’s first partner commits suicide

Alex said that he had never known anyone prior to becoming a cop who had committed suicide, even in the military. His first partner was named Frank. “We bonded when we were rookies in Rampart Division. We were good friends.”

They first met on a brutal shooting of a man near MacArthur Park. The victim was carjacked and shot in the face. Both Alex and Frank were with their training officers when they found the man. What Alex remembers most is the enormous amount of blood flowing from the man’s mouth, an image he cannot erase no matter how much booze he consumes or sex he engages in. They pursued the killers on a 100-mile-an-hour chase, with Alex and Frank in the lead cars. The driver bailed out of the car and they chased him down, beat him and arrested him.

Alex and Frank talked about that incident whenever they met for drinks. Eventually, Frank moved on to Foothill Division and Alex went to Wilshire. As partners, they had shared a lot about their hopes and dreams. When Alex was about five years on the force, he was told that Frank shot himself in the mouth with his 9mm. “I was in disbelief because this was a guy I had ridden with, and we had spent a lot of time talking and laughing and joking around.”

Alex said that Frank had shot someone during a confrontation and he was being investigated for possible unjustifiable homicide. Then his wife said she was going to leave him and “that’s what caused him to eat his gun.”

Alex blamed himself. “Maybe I could have talked to him. I was out drinking at Club Fantasia when I heard the news from one of the academy instructors who was working the door. I called my mom, crying, babbling, ‘Mom, Frank is dead, Frank is dead.’” His mother was frightened because she knew he was drinking and feared he might do something foolish.

Alex could not come to grips with Frank’s suicide. If Frank could kill himself, a cop Alex considered stable, then anybody could.

Another partner commits suicide

In a short time, another police partner committed suicide. Alex was told that the cop who brought his girlfriend down to the station to strip for the other men had killed himself and Alex was devastated with grief. “He hooked up with this woman and ended up killing her and then himself in a murder-suicide. It wasn’t a normal relationship. What guy is going to have his girlfriend strip in front of his friends? She wanted to leave him and he could not take the rejection.”

Four more friends kill themselves

The suicides of his partners affected Alex profoundly, but four more officers he knew killed themselves. One killed himself on the day his ex-fiancé got married. Another killed himself over a woman who left him. The fifth suicide was one of his academy instructors. He had testified against the officers involved in the Rodney King affair and said they had used excessive force. He was called a betrayer and this depressed him. The sixth suicide was a gang officer who killed himself in his garage with carbon monoxide over a love relationship gone bad.

Most of the suicides were over relationships. “When a police officer loses a relationship, they feel like they are helpless, losing control over everything,” said Alex. “If nobody loves me, what good am I?”

Suicides as modeling behavior

For Alex, the suicides were modeling behavior. They demonstrated that if things got too tough, suicide was always an option. His partners did it. His friends did it. Many victims he had investigated did it. Why not him?

Alex felt that the department wanted “to throw me away after I had almost gotten killed trying to stop a robbery, doing the right thing. I thought, Wow, I’m a loser, I cheated on my wife, I cheated on my whole family, I’m fucked up, I have all these multiple relationships. My life is chaos. I always thought that I would lose it at some point. I could blow up or snap at any moment.”

Remarried, arrested for domestic violence

During his undercover period at South Bureau Narcotics, Alex slept with many women, but dated one particular woman who he married in 1997. Six months after the wedding, they had an argument about a video camera locked in her car. Alex tried to take her car keys, but she resisted and he bit her hand. He said there was no blood, but her sister-in-law called the police and Alex was charged with domestic violence.

The incident made him realize he was losing control of his personal life and acting irrationally. He was exhausted, depressed, suffering from PTSD symptoms and self-medicating on alcohol and sex. The domestic violence charge was a black mark on his police record. Now he would never be promoted and he saw his life spiraling down. He thought, “Shit, my career is over. What am I gonna do? What am I gonna be?”

The charge was dropped as baseless, but a few days later, he was told that his wife was cheating on him. He was cheating on her, but he was too enraged to see the irony, and he became jealous and obsessive.

He began following her to find out who she was sleeping with. She reported to the police that he was stalking her. “And I was—because I wanted to know if it was true. I finally caught her with the enemy, a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Deputy.” Today he laughs at that last statement, but he wasn’t laughing then.

“That pushed me over the edge. Forget that I was cheating on her, the manly, macho double standard. Oh, hell no,” he said. “I saw myself as the victim and I smashed the windows of this poor guy’s car.”

Second arrest—for making terrorist threats

That destructive act, along with the stalking charge filed by his wife, caused the LAPD Internal Affairs Department to open an investigation and they started surveilling him. “From being the stalker, I became the stalked by my own department.”

When Alex was working an off duty security job at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, he noticed an unmarked car drive by several times and realized he was being watched. “So I went up to the unmarked car and asked the detective what his fucking problem was.”

The officer called for backup. Five or six units arrived and officers from the Special Operations Section of Internal Affairs (SOS) “surrounded me with orders to get on the ground. Pissed off, I gave them the finger and told them, ‘Fuck you! Take me down motherfuckers.’” And they did.

Alex was arrested for making terrorist threats and held on $1 million dollars bail. He spent four days in jail before the charge was dropped and he was freed.

After the incident, Alex was mortified. He told the LAPD therapist that he was suicidal. He thought the department saw him as a psycho cop and his career was over.

Alex resigned, not knowing what he would do or who he was anymore. His second marriage of about six months was annulled.

Diagnosed with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

It was fortuitous that Alex left the department when he did. If he had tried to tough it out as a police officer, he may have ended up committing suicide over unresolved issues. He was seeing an outside therapist and it was at this point he was diagnosed with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Suddenly, all his incomprehensible actions made sense. Seeing his drinking and sex addiction through the lens of PTSD, he understood how the traumatic incident where he was attacked and nearly killed, inflamed by memories of previous traumas as an undercover agent and patrol officer, combined to make his life a living hell of obsession, self-medication and reckless bravado.

Wasn’t told he had PTSD

Several years after Alex had left the department, he had a discussion with the department’s psychologist who had treated him for five years. The psychologist admitted that he knew Alex had Posttraumatic Stress Disorder as a result of the traumatic incident and because of a buildup of incidents throughout his career, but was not allowed to tell him because of liability issues.

If I hadn’t heard this claim before, I would be shocked. But ever since I started my research on CopShock in 1993, I’ve heard the same condemnation from dozens of traumatized officers around the country. Usually the complaint was about small departments that refuse to recognize PTSD to prevent paying out pensions. This is the first time I’ve heard it about the LAPD. “They would rather have me act out and think I was losing my mind and maybe commit suicide than to tell me,” Alex said.

Knowing the PTSD diagnosis early on would have helped Alex understand his behavior and suicidal thinking. It would have stopped his descent into sex addiction as a self-medication tool.

How Alex dealt with his sex addiction

In due course, the outside therapist who diagnosed Alex with PTSD also identified his sex addiction and helped Alex address the issues.

In addition, Alex researched other sources to help himself better understand what he was experiencing so he could manage his symptoms. He read psychology books like Dr. Patrick Carnes’s groundbreaking sex addiction book, Out of the Shadows, researched sex addiction websites and tried to identify his compulsive and self-destructive patterns.

“Dealing with my sex addiction has been a lifelong process,” he said. “There is no magical cure and you are not miraculously healed. What helped me is introspection, being honest about my life, and understanding the path of how I got here. Getting rid of the shame and guilt has been difficult because of the people I have hurt.”

There is little doubt that Alex suffered from sex addiction as it is currently and hesitantly defined, and he cannot say for certain that he has overcome it.

He displayed the typical symptoms: an inability to control his sexual behavior, an unwillingness to face the harmful consequences of his actions, a need to have more frequent indiscriminate sex with more and more women, and a feeling of deprivation when he couldn’t have sex.

His compulsive behavior interfered with his personal and work life, and his sexual activities caused severe stress on his loved ones and friends. He lived for the intense emotional arousal and adrenaline rush that sex gave him and the soothing calm afterwards. He was constantly looking for someone to have sex with, and spent many hours of his day in pursuit of that goal. He was engaged in the vicious cycle of stress, release, shame, anxiety—and the need to do it all over again.

About a year after Alex left the LAPD, he opened All American Investigations, a Los Angeles private investigation and security firm, which is highly successful (www.cops4hire.com). He has started a website to help police officers with issues such as sex addiction, PTSD, alcohol abuse, and to provide current news stories affecting law enforcement. Please see www.RenegadePoPo.com. He was willing to talk about his sex addiction for this article as a way of helping officers who are struggling and too embarrassed to reveal their compulsive and harmful behaviors.

Conclusions

We can’t say with certainty that sex addiction is a symptom of PTSD or that it could lead to suicide. However, it appears to be an outcome of severe unresolved psychological, emotional, physical or sexual trauma. Perhaps the American Psychiatric Association may wish to examine sex addiction more closely for future editions of the DSM.

A disturbing part of this discussion is the seemingly predatory behavior of some police officers toward women. According to Alex, they were constantly on the prowl at clubs, bars and even in the homes of victims of domestic violence. Most officers are men with male urges, but this is beyond being young, stupid and libidinous. Predatory behavior crosses the line for professional police officers, even if women are making themselves readily available. It shows not only disrespect for women, but also disrespect for themselves, their families, and the badge they honor.

Treating sex addiction seems to require therapies beyond the usual treatment for standard addictions. For instance, the usual treatment program for alcohol and drug dependencies begins with total withdrawal, something that cannot be done with sex. Perhaps that is why sex addiction has a high relapse rate.20

However, there are many addiction clinics that offer treatment programs designed for the sex addict. Among the finest are:

Sexual Recovery Institute (SRI), Los Angeles, CA

The Sexual Recovery Institute (SRI) of Los Angeles, CA, offers a number of specific programs for sex addiction sufferers such as a 12-Step Program, a two-week residential program, individual treatment, and telephone and online webcam services, as well as online support group meetings and weekly sexual recovery chats (www.sexualrecovery.com). On its website, the SRI provides a confidential Sexual Screening Addiction Test for both men and women at www.sexualrecovery.com/resources/self-test/gsast.php.

Sierra Tucson, Tucson, AZ

Among other things, the Sierra Tucson treatment center treats sexual addiction, as well as PTSD and the effects of abuse and trauma. At the same time, they treat chemically dependent individuals. Patients are offered educational and therapeutic groups specific to their situation. For example, their Sexual Compulsivity Group provides therapy for people with sexual addiction/compulsivity and sex and love addiction. One of the therapies used is called EMDR or Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, as well as other successful therapies. Many police officers I’ve talked to who have undergone EMDR therapy speak very highly of its effectiveness. In addition, Sierra Tucson provides 12-Step meetings, individual attention and several grief and therapy groups. You can see more at www.www.SierraTucson.com.

Pine Grove Health and Addiction Services, Hattiesburg, MS

Under the direction of Dr. Patrick Carnes, a world renowned addiction specialist, Pine Grove’s Gentle Path program helps those suffering from sexual addiction, among other things. The Gentle Path program provides diagnostic assessment as well as a six-week intensive program to treat sex addiction. At the same time, residents are treated for anxiety, past traumas and other addictions such as chemical dependency. As at other treatment centers, Pine Grove offers EMDR therapy. For more about this exceptional program, please go to www.pinegrovetreatment.com/gentle-path.html.

The Sexual Recovery Institute, Sierra Tucson and Pine Grove Health and Addiction Services are only three of many good treatment centers that provide therapy and services for people who are sex addicts. Please check them out thoroughly before committing to a program to make sure that center is right for you.

Sex addiction in stressed-out police officers is a relatively new field that requires a great deal more study. At the moment, we don’t know how widespread it is. It is my hope that this article will inspire mental health professionals to conduct further research.

Footnotes

1. DeFrank, Thomas M. (2007) Write It When I’m Gone: Remarkable Off-the-Record Conversations with Gerald R. Ford, p138. New York: Berkley Books.

2. James, Susan Donaldson. (2010, November 29) Tiger Woods Effect: More Sex Addicts Seek Help. ABCNews.com. Retrieved October 14, 2011, from http://abcnews.go.com/Health/MindMoodResourcesCenter/sex-addicts-seeking-treatment-jumps-50-percent-tiger/story?id=12237598.

3. Weiss, R. (2011). Sex Addiction, Schwarzenegger and Strauss-Kahn: Understanding Men in Power Who Sexually Act Out. Psych Central. Retrieved October 26, 2011, from http://blogs.psychcentral.com/sex/2011/05/sex-addiction-schwarzenegger-andstrauss-kahn-understanding-men-in-power-who-sexually-act-out/.

4. Boston Globe Staff. (2005, July 31) Wade Boggs: 2005 Hall of Fame Inductee, Nothing average about five-time battling champ. Boston.com. Retrieved October 28, 2011, from http://articles.boston.com/2005-07-31/sports/29213277_1_red-sox-hall-of-fame-today-jdrry-remy.

5. Doane, Seth. (2010, June 3 Update) The Stories Behind Sex Addiction. CBS News. Retrieved October 24, 2011, from http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2010/01/24/sunday/main6136039.shtml.

6. Peele, Stanton. (2009, December 13) Will Sex Addiction Be in DSM-V? Psychology Today. Retrieved October 28, 2011 from http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/addiction-in-society/200912/will-sex-addiction-be-in-dsm-v.

7. Goodman, MD, Aviel. (2009, May 26) Sexual Addiction Update, Assessment, Diagnosis and Treatment. Psychiatric Times, Vol. 26 No. 6.

8. James, Susan Donaldson. (2010, November 29) Tiger Woods Effect: More Sex Addicts Seek Help.

9. Carnes, Ph.D., Patrick. Definition of sex addiction, retrieved October 27, 2011, from www.sexhelp.com/addiction_definitions.cfm.

10. James, Susan Donaldson. (2010, November 29) Tiger Woods Effect: More Sex Addicts Seek Help.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. The Society for the Advancement of Sexual Health (SASH). Information retrieved October 26, 2011, from http://www.sash.net. See also: Sex Addiction Statistics and Facts, retrieved October 26, 2011, from www.myaddiction.com/education/articles/sex_statistics.html.

14. Kates, Allen R. (2008) CopShock: Second Edition, Surviving Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), p209 . Tucson, AZ: Holbrook Street Press.

15. Ewald, Roschbeth. (2003, May 13) Sexual addiction. AllPsych Journal, retrieved October 28, 2011, from http://allpsych.com/journal/sexaddiction.html.

16. Salazar, Alex. Case history of former LAPD police officer Alex Salazar. Information gathered from audio-taped interviews, discussions and emails conducted by Allen R. Kates, MFAW, BCECR, during October, 2011.

17. Dillow, Gordon. (1991, October 7). Alex Salazar: A cop doing his duty. Downtown News: Los Angeles, CA.

18. Bacardi 151 rum. Retrieved October 26, 2011, from http://www.drinksmixer.com/desc185.html.

19. Gilmartin, K.M. (1986) Hypervigilance: a learned perceptual set and its consequences on police stress. In J.T. Reese & H.A. Goldstein, (Eds.) Psychological services for law enforcement (pp. 445-448). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. See also: Kates, Allen R. (2008) CopShock: Second Edition, Surviving Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), p112.

20. James, Susan Donaldson. (2010, November 29) Tiger Woods Effect: More Sex Addicts Seek Help.

For Further Study

Cross, Chad L. Ph.D., Aschley, Larry, Ed.S., LADC. (2004, October 28) Police trauma and addiction: coping with the dangers of the job. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, Vol. 73, Issue 10, pp.24 to 32. Retrieved October 28, 2011 at http://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=207385.

This article describes responses to trauma and stress, the link between trauma and substance abuse, and strategies for breaking the cycle of trauma and substance abuse.

To Trauma Support Sources

Back to Home Page

To Top of Page

Copyright © 2008, 2025 by Allen R. Kates